Insects and Wildflowers of California Chaparral

– California’s Wildland-Urban Interface

by Donna M. Walker

Growing up in San Diego’s South Bay, I found being outdoors very healing and soothing to my sensitive nature, especially as a teenager.

I was one of those kids who could easily entertain themselves.

I’d get especially excited when I spotted a horny toad lizard (I learned much later that it’s called a ‘Coast Horned Lizard’ Phrynosoma coronatum).

Another favorite pastime was to catch bees in a jar with holes poked into the lid, for observation of course, and then let them go.

The wildflowers I picked and brought home to my mom (she’d always smile and tell me they were beautiful) were from a community of California native plants called, “Chaparral” (one p, two r’s). From an early age, I appreciated nature and every path I took was an adventure.

Did you know that honeybee’s live for just 5-6 weeks and during their lifetime, they change careers several times? To find out more, visit our blog: Worker Bees and the Role of the Drone.

Across the street from where I lived were an open field, a railroad track, and a pond just beyond the track, where I fished for tadpoles.

The field and pond, alas, are no longer but instead, are overgrown with homes and other buildings and – parking lots.

Fortunately, there are still open areas of natural habitat where chaparral and wildlife abide.

Depending on where you live, there are also protected areas with lots of trails for walking, hiking, and bicycling.

Many of these recreational reserves have visitor centers where you can take free nature walks and learn about our local chaparral plants and flowers, and wildlife.

If you’ve never been introduced to a monkeyflower and experienced its tongue sticking out at you … well, you’ll just have put this one on your bucket list. …

Nature around here is beautiful, and a lot closer than you think.

Come, take a walk on the wild side (no pun intended) and let me show you just what you’ve been a missing. …

But first, let’s talk about this unique ecosystem of ours, “chaparral.” People often wonder, “What exactly is chaparral?”

Next time you’re driving along the freeway, take a look at the hillsides; see all those green shrubby trees? Notice I said shrub not “brush” (I’ll explain later).

Chaparral consists of several distinct communities of native plants and shrubs that are drought-hardy and grow in a Mediterranean-type environment like we have here in southern California.

Some chaparral communities are denser than others.

Each with unique characteristics, each important to our birds and bees, butterflies and lizards, and other neat critters.

California Sagebrush is one of the communities of chaparral found on the coast and inland areas, maybe even in your own backyard.

You’ll find these native plants and shrubs have fragrant leaves and beautiful wildflowers. Some of the plants are green all year round while others become dry during the summer.

Chaparral is California – our largest and most extensive ecosystem!

Further inland, into the foothills and mountains, you’ll find the red bark and berries of Manzanita, some Mountain Mahogany, Scrub Oak, and many other types of hardy shrubs.

California Here We Come … Wildland Meets Urbanscape

One of the things that attract people to California, besides the weather, is the spacious feeling and open views of canyons and fields near our home.

We like the feeling of having that space; even when driving from city to city, there’s so much scenery to see and enjoy.

But, with that being said, many of us live in what’s called a “wildland-urban interface.”

The “wildland” is California’s chaparral adjacent to many of our residential areas, including some businesses.

When we choose to live on the edge of town or next to canyons and rolling hillsides, with that choice comes a certain responsibility.

A home situated in a wildland-urban interface shares living quarters with the native plants, of which some do become dry and brittle during summer, and sharing the land next door also includes local wildlife, spiders, and insects.

It also means one should have a good fire insurance policy in place.

A Word on California Fires and Chaparral

There are many misconceptions about chaparral. The one most often touted, especially by newscasters, is that California chaparral is “adapted to fire” and “needs to burn.”

You’ll hear them call our unique ecosystem of chaparral, “brush that fuels fire.”

The Truth: California suffers from too much fire, and it’s not from natural causes but by humans.

Prescribed burning to a natural landscape, already suffering, is totally unnecessary.

Fire, be it started by accident or on purpose has led to a loss of insect and native plant species, animal life, and unfortunately, some human life as well, not to mention our homes.

California chaparral is not adapted to fire but is adapted to a particular “fire pattern.” Chaparral’s natural fire pattern, is to only experience fire between 35 to 150 years.

Living here in southern California, you know it’s more like every 2 – 4 years!

After a fire, it’s true, you will see some green growing along the hillsides but that doesn’t mean native plants are coming back; the green you see are invasive weeds and grasses, which do, in fact, contribute to fires.

Truths and Myths about Chaparral

Myth: Chaparral is nothing but fuel for California wildfires and should be eradicated from open areas of land.

Truth: Chaparral is where Californians go to be in nature! It’s not “brush,” as news anchors refer to it but a diverse and rich ecosystem of different plant communities within our state.

Myth: Chaparral is just a fancy word for ugly, dried up, weedy-looking plants.

Truth: Chaparral is a beautiful, shrub land habitat teeming with wildflowers, animals unique to California, and interesting insects.

Our native Quino Checkerspot butterfly almost became extinct because of the reduction in chaparral.

Fact – Chaparral can be found in every single county in California from the coast and inland areas where a mixed community of chaparral, sometimes referred to as “soft chaparral” exists, to mountainous regions upward of 5000 ft.

Fact – Cleveland National Forest is not your typical “forest” at all but 90% chaparral!!!

Fact – Invasive plants, grasses, and weeds are what “fuel” fires.

OK, I’ll get off my soapbox … so let’s get back to the wildflowers and insects.

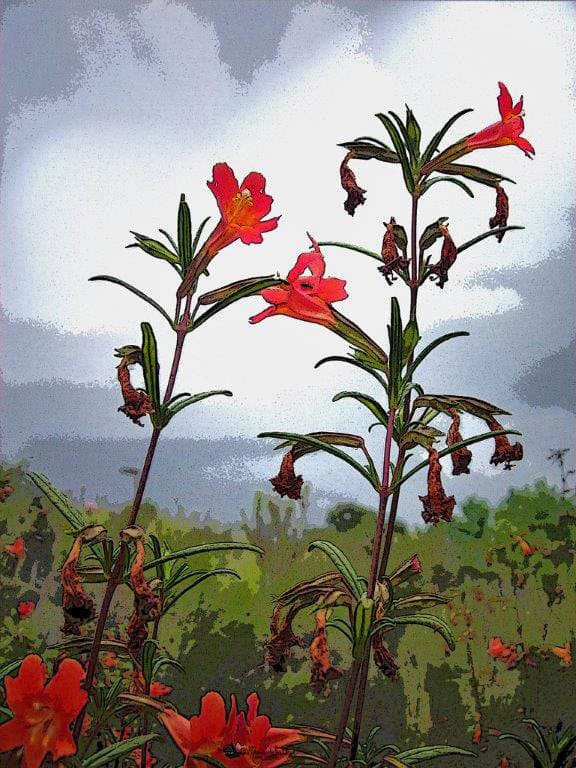

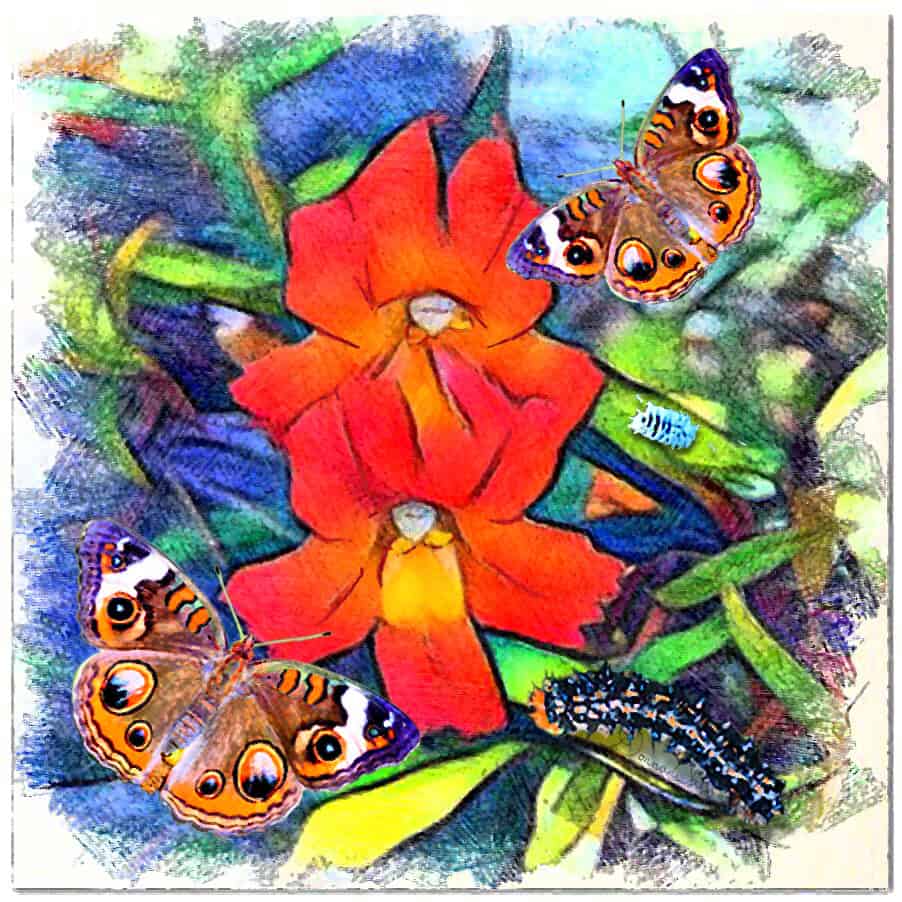

Meet the Monkeyflower and its Pollinators

The Sticky Monkeyflower (Mimulus aurantiacus) also known as “Bush Monkeyflower,” is supposed to look like a monkey sticking its tongue out. The leaves are sticky, ergo – “Sticky Monkeyflower.”

Early Native Americans would grind the sticky leaves into poultices for wounds.

The flowers are edible. Imagine pretty red, orange, and yellow monkeyflowers garnishing your salad. …

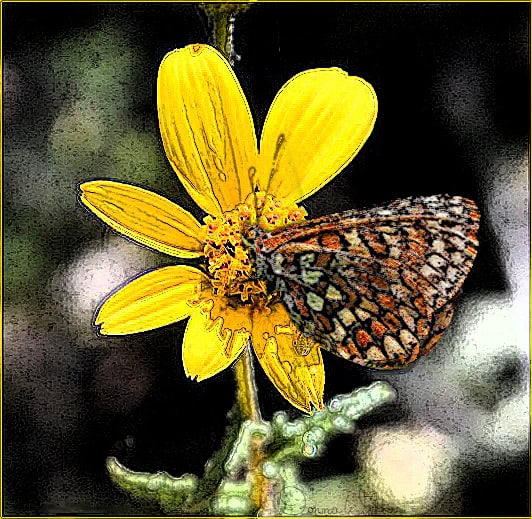

Frequent pollinators and nectar sippers such as the Buckeye and Checkerspot butterfly enjoy Sticky monkeyflowers as do other insects and hummingbirds.

Quino Checkerspot – Southern California’s Endangered Butterfly

The Quino Checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha quino) is so tiny; its wingspan is only about an inch and a half to two inches in length. Its habitat is our chaparral, specifically California plantain.

The number of Quino Checkerspots has declined to a critical point of near extinction, placing the butterfly on the federal endangered list.

This is a result of climatic changes but the real culprit – real estate. More and more of Quinos’ native habitat are disappearing due to real estate development.

One needs only to drive up and down the 15 freeway to see pockets of new homes, strip malls, and other buildings encroaching into our chaparral communities.

Here’s some good news; over the last several years, scientists have been able to raise Quino larvae and successfully reintroduce the endangered butterfly within both San Diego and Los Angeles Counties.

The loss and decline in numbers of such species is evidence of how important it is to keep portions of our lands in their natural state.

If it wasn’t for the undeveloped land that we do have, to the east of Los Angeles and in San Diego County, the Quino Checkerspot would have nowhere to go and would definitely become extinct.

Argentine Ants and the Plight of the Coast Horned Lizard

In Argentina and Brazil, Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) have natural enemies that keep their population under control but in the U.S. there are no “natural” enemies for Argentine ants.

How could these tiny little ants affect our Coast Horned Lizard?

California Seed Harvester Ants (Pogonomyrmex californicus) are the main source of food for Coast Horned lizards.

Harvester ants are several times the size of Argentine ants with very large heads.

Argentine ants are just too tiny to make a worthwhile meal but that’s not the reason why Coast Horned Lizards are listed as a threatened species …

Argentine ants are fighters. They’re mean and vicious and wage war over food resources with our native ants.

These invaders from South America will actually lie in wait for harvester ants to pass by, then attack, and proceed to dismember the harvester ants, limb by limb.

Because Argentine ants have taken over much of our native ant territory, the numbers of our Coast Horned lizard have declined significantly.

If you do come across one, my hope is that you’ll realize how lucky you are and appreciate this cool, “horny toad lizard.”

While we’re on the subject of Argentine ants, you may have noticed that they’ve become year-round pests. Just when you think you’ve got them under control, a new line pops up somewhere else in your house.

You can read more about these invaders and why they’re so hard to control with “Do-it-Yourself” methods on our page: Argentine Ants

Prickly Pear Cactus and Cochineal Scale Insects

If it wasn’t for the prickly pear cactus, there wouldn’t be any cochineal insects, and Michelangelo’s paintings wouldn’t have the deep crimson reds which were obtained by harvesting these faceless insects.

Not only did early artists use cochineal as paint, the insects were harvested by hand during the 1600-1700’s and exported for use as a red dye in rugs and clothing. These bugs were in such demand, the Spanish got rich from keeping their location a secret.

Cochineals are still used today for dye, in some parts of the world but right here in the U.S., they’re harvested to color our food! If you see the word “Carmine” as an ingredient, you’re eating bugs!

Next time you’re at the grocery store, take a gander at the yogurt isle, specifically pink colored yogurts – strawberry for example, and check out the ingredients.

Read more on our blog: Bugs in Your Food – Cochineal, A.K.A. Carmine for the full story on prickly pear cacti and the cochineal insect.

Now let’s take that nature walk … here are just a few of the beautiful flowering plants in our California chaparral communities:

Wildflowers of California Chaparral

As you walk, listen to the sounds of the birds in the chaparral. Keep your eyes open for blue-belly lizards doing push-ups. Pause and investigate harvester ants as they carry seeds to their nest.

Stop to smell the wildflowers … and guess what will happen? You’ll feel calmer but energized – you’ll lower your blood pressure too!

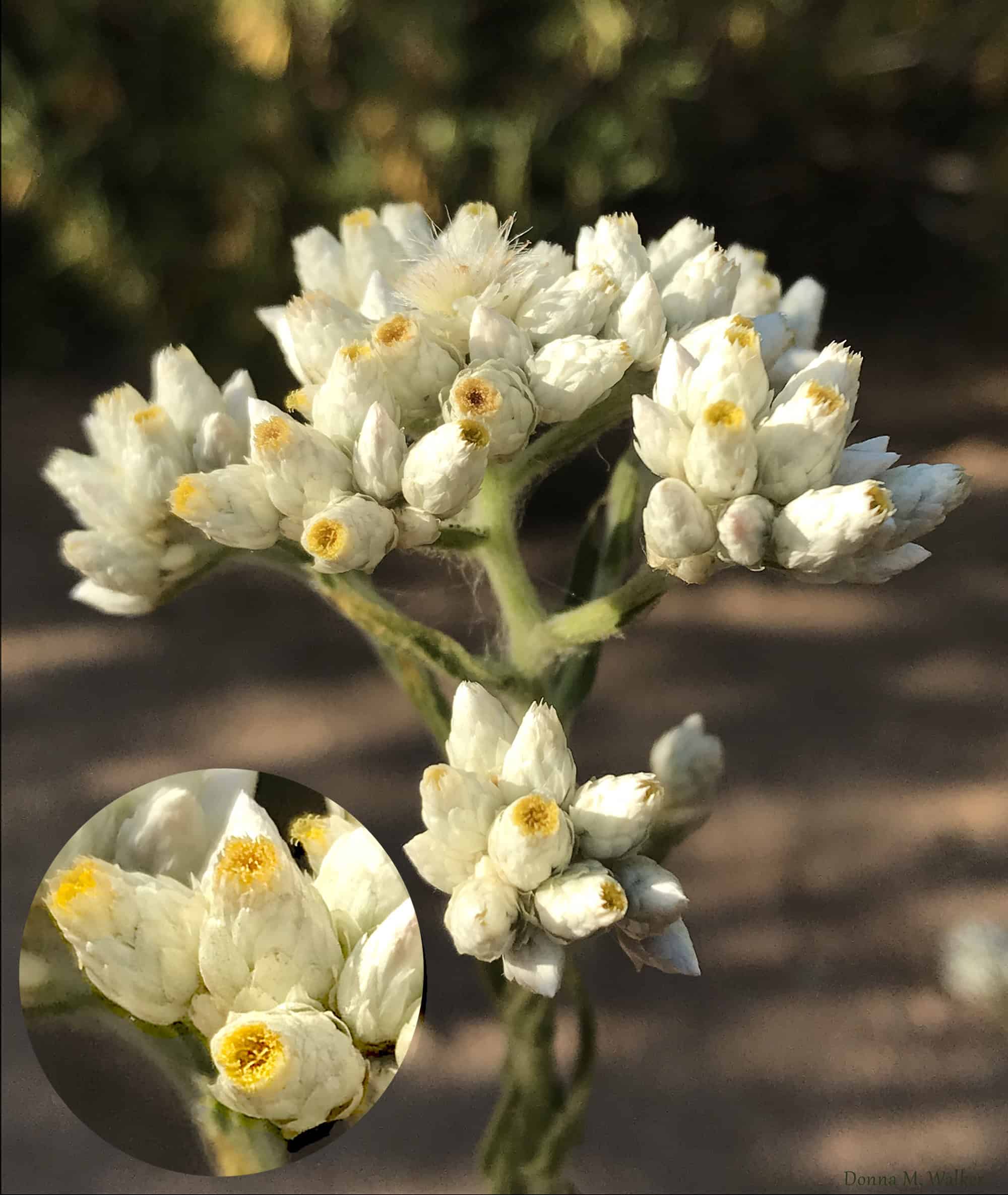

California Cudweed / Everlasting Pearl (Pseudognaphalium californicum)

Indian Paintbrush – Wavy Leaf Paintbrush (Castilleja applegatei)

Lemonade Berry (Rhus integrifolia) – Sour berries really taste like lemon!

Chaparral Bush Mallow (Malacothamnus fasciculatus)

Deerbrush Ceanothus (Ceanothus integerrimus)

Toyon Berry A.K.A. California Holly and Christmas Berry (Heteromeles arbutifolia)

Honeybee on Black Sage (Salvia mellifera)

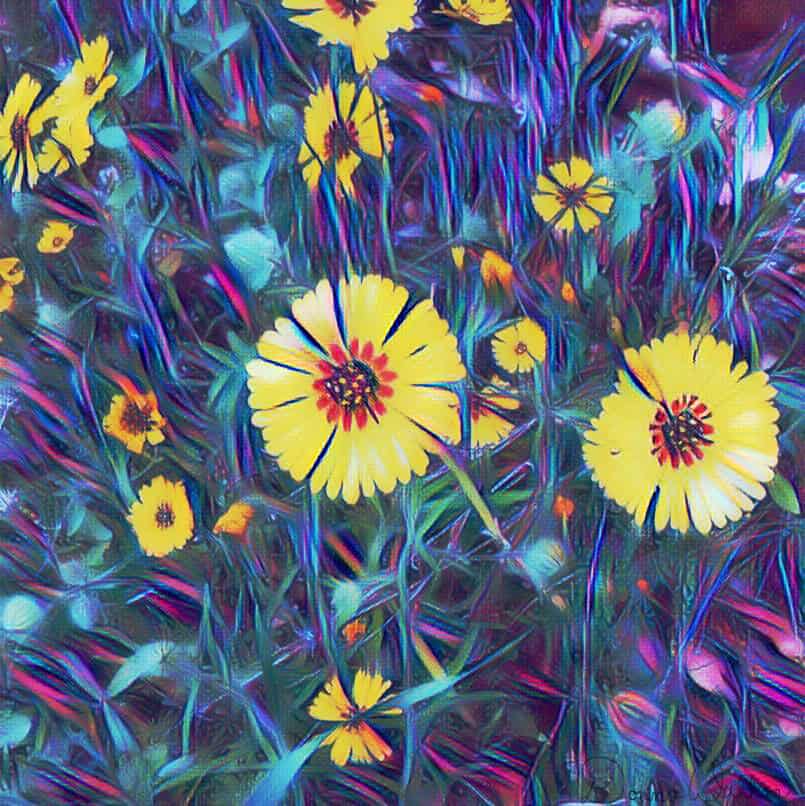

Common Madia (Madia elegans)

Chaparral Yucca “Our Lord’s Candle” (Hesperoyucca whipplei)

So, how was your walk through California’s chaparral? See what beauty you may have been a missing. …There is a growing awareness, thankfully, among Californians of just how important chaparral communities are – to both wildlife and humans.

Preserving these lands protects our native plants and animals, while at the same time, providing areas for two-legged creatures to enjoy a few recreational activities.

Chaparral is essential to our watersheds, wildlife habitat, grazing areas for livestock, and human fun and adventure.

I hope you come to see our hillsides, canyons, and fields a little differently.

Take a walk or hike with one of your local nature preserves – they’re free! Or, if you’re fortunate to live on the outskirts of town, try some nearby trails … make it an adventure and see what you can see.

In the words of Dr. Seuss:

“You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself any direction you choose.

You’re on your own. And you know what you know. And YOU are the one who’ll decide where to go…”

– Dr. Seuss’ Oh, The Places You’ll Go!

A word about Hearts Pest Management:

Hearts is an environmentally conscientious company.

We are the only southern California pest control company to win California’s E.P.A. (Environmental Protection Agency) Innovator Award in Integrated Pest Management (I.P.M.).

And, the first to specialize in Green / Organic Pest Control. There is a reason why we have the word “Heart” in our name … we are a company with heart!

References / Acknowledgements

California Chaparral Institute. 2018. Fire and Nature. Visit this amazing and informative website at:

California Chaparral Institute

Fire Photo Credit – Supervisor Park Ranger Jeff Anderson, Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve, Escondido, CA

Free Nature Walks! Visit: https://elfinforest.olivenhain.com

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2002) ‘Quino Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas editha quino) survey’ Carlsbad, CA

Baker, Debbi (2016). ‘Endangered Butterfly Could Get New Lease on Life at San Diego Zoo’ Los Angeles Times 18, April.